In-Q-Tel: Imitating Intelligence & Innovation

Behind the Intelligence Community's "Innovation Engine" that has invested in 750+ startups, created 50+ Unicorns, and has transitioned 500+ technologies to an intelligence use-case.

What is the common thread that ties together a diverse group like Twelve Labs, Google Earth (fka Keyhole), Mapbox, Orbital Insight, and Palantir?

It's not their technology, their founders, or even their specific market sectors.

Instead, it's a less obvious connection – they have all received funding or backing from the enigmatic government venture capital firm In-Q-Tel.

In the wake of the dot-com bust of the early 2000s, when tech startups were considered anything but "cool" and investors were running scared, In-Q-Tel emerged as a contrarian player funded by the U.S. Intelligence Community1 that wasn't just chasing financial returns, but was strategically investing in companies that could advance national security.

Over the years, In-Q-Tel has consistently and quietly, for more than two decades, identified and nurtured startups pushing the boundaries of intelligence-focused technology (even dual-use ventures as a whole) and its applications. This model, which is a blend of DARPA-esque innovation with venture capital incentives, provides a crucial path for companies that are not only developing groundbreaking tech but also advancing US national interests.

But how does a seemingly innocuous investment firm, named after a fictional spy's research division—a mashup of "intelligence" and "Q," James Bond's gadget supplier—become a key player in a global web of surveillance, data analysis, and cyber warfare?

How has the CIA, through In-Q-Tel, been able to actively 'capture technological innovation' at its source in Silicon Valley?

In this article, we delve into IQT's origins in the late 1990s, tracing its creation to a visionary group of leaders who recognized the need for the IC to tap into the rapid innovation of the private sector. From there, we will dissect IQT's unique business model, examining how it differs from traditional venture capital and how it's structured to align with the specific needs of its government sponsors. We'll analyze the organization's operational framework, including the crucial role of the In-Q-Tel Interface Center (QIC) and the "Q Process" for technology development. A key focus will be understanding how IQT drives down technology acquisition costs for the government, leveraging a "Semi-Napkin Math Model" to illustrate the cost savings. Furthermore, the article will compare IQT to other government-sponsored investment initiatives, highlighting the factors that contributed to IQT's success where others have faltered.

There is also a personal motivation behind this: For those that know me, will know how much I admire In-Q-Tel and the model that the non-profit government VC fund they operate under. [Encapsulated in the Author’s Note at the end.]

A. The Inception of “In-Q-Tel”

The birth of In-Q-Tel is actually a tale of two contrasts: on one hand the simmering, wildfire-like innovation at Silicon Valley in the midst of the dot-com boom, and on the other hand, the CIA straggling behind caught up in a quagmire of red-tape and bureaucracy.

The history is nebulous, at best, having enough precedents and pivotal moments to perhaps fill a binge-worthy Netflix series spanning several periods. However, if there is a singular inflection point that ‘birthed’ IQT? It would go something like this.

As with any inflective point in the history of mankind, the story of In-Q-Tel's genesis is as much about the people as it is about the institution. It's a story of individuals who recognized a looming threat and dared to forge a new path.

And then there were 5 (+11)2

[1] Ruth David: The Catalyst for Change

Before In-Q-Tel could be conceptualized, there was a growing sense of unease within the CIA, a feeling that the agency was losing its technological edge. The individual who recognized this most acutely, and who possessed the intellect and drive to address it, was Dr. Ruth David. She arrived at the CIA in 1995, not as a career intelligence officer, but as a scientist forged in the crucible of academia and national laboratories. She was an outsider, and perhaps that's precisely what the CIA needed.

"I had to ask for Internet access on my desktop," she later recounted, highlighting the agency's isolation from the burgeoning digital world.

Unlike her predecessors at the Directorate of Science and Technology (DS&T), David came from Sandia National Laboratories, where she had spent two decades immersed in cutting-edge research, and authoring numerous technical papers. She even taught graduate courses in electrical engineering at the University of New Mexico. This background gave her a unique perspective, one that was unburdened by the CIA's traditional (and often cumbersome) ways of doing things. It instilled in her a deep appreciation for the power of collaboration and the vital importance of staying at the forefront of technological innovation.

David's appointment as the first female director of the DS&T was, in itself, a groundbreaking moment. But it was her actions, not her title, that truly defined her legacy.

She took the helm of the DS&T during a period of immense upheaval. The Soviet Union had collapsed, and with it, the familiar contours of the Cold War. The CIA was facing budget cuts, a talent drain to the booming private sector, and a new breed of adversaries who were leveraging emerging technologies in ways that the agency was ill-equipped to counter. The DS&T, renowned for its innovative work during the space age, needed to adapt, and David understood this better than anyone.

She was, as then-DCI George Tenet aptly described her, "smart, bold, and agile." And she wasted no time in putting those qualities to work. David quickly recognized that the DS&T needed to reorient itself to a world where information technology was king. She championed initiatives to transform the directorate into a national laboratory and a center for scientific and technological excellence, fostering collaboration within the CIA and across the broader intelligence and defense communities.

But David's most significant contribution was her unwavering belief in the need to engage with the commercial world, particularly the burgeoning tech hub of Silicon Valley. She saw that the most significant advances in technology were no longer happening within the confines of government labs, but in the garages and startups of entrepreneurs. She envisioned a future where the CIA could tap into this wellspring of innovation, adapting commercial technologies to meet the unique needs of the intelligence community.

David's tenure was also marked by a sense of humor and approachability, a stark contrast to the often-stuffy atmosphere of the intelligence world. One anecdote perfectly encapsulates this: during a visit by some of America's top young scientists, David was asked, "So, where do you keep the aliens?" With a twinkle in her eye, she quipped, referring them to the U.S. Air Force, demonstrating her ability to connect with people from all walks of life and her understanding of how to navigate even the most unusual questions with grace.

By the time she left the CIA in 1998, Dr. David had laid the foundation for a technological renaissance within the agency. Her initiatives, particularly her focus on building partnerships with the private sector, paved the way for the creation of In-Q-Tel. She was the architect of a new approach to intelligence, one that recognized the need for collaboration, agility, and a constant pursuit of innovation. Her legacy is not just in the technologies she championed, but in the cultural shift she initiated, a shift that continues to shape the CIA to this day. She was more than just a director; she was a catalyst for change, a trailblazer who dared to challenge the status quo and, in doing so, helped to redefine the future of American intelligence. It was this foresight and boldness that earned her the Agency's Distinguished Intelligence Medal, a fitting tribute to a woman who transformed the CIA's approach to technology and national security.

[2] George Tenet: IC Veteran-turned-Innovator

While George Tenet's legacy is undeniably intertwined with the controversies of the Iraq War, his role in the creation and early success of In-Q-Tel is a crucial, often overlooked aspect of his tenure as DCI. He was not the initial visionary—that credit belongs to Ruth David—but he was the champion who recognized the potential of her radical idea and provided the leadership necessary to bring it to fruition. He embraced the concept of In-Q-Tel..

George Tenet, a seasoned intelligence officer, understood the gravity of the situation when he took the helm of the CIA in 1997. He inherited an agency struggling to adapt to a post-Cold War world, facing budget cuts and a growing technology gap. Tenet, however, was not one to shy away from a challenge. He recognized the need for a radical departure from the status quo. He saw in David's vision a path towards revitalizing the agency & championed the idea of a CIA-backed venture capital firm, providing the crucial top-level support that would be needed to overcome bureaucratic inertia and skepticism within the very intelligence community that IQT looked to serve. He provided the executive muscle to turn David's radical concept into a reality.

[3] Alvin “Buzzy” Krongard: Linking Washington to Wall Street

Alvin "Buzzy" Krongard [often referred to as “Buzzy the Banker”] was a different breed altogether. A former Marine with a Princeton pedigree, he was a Wall Street veteran, the tough-talking CEO of Alex Brown Inc., an investment bank known for its early bets on tech giants like Microsoft and AOL.

Krongard brought to the table not only a deep understanding of finance but also an insider's knowledge of the burgeoning tech landscape. He knew how Silicon Valley operated, its culture, its drivers, and its key players.

When Tenet brought him on board, first as a counselor and later as executive director, Krongard immediately recognized the potential of David's idea. Krongard was not afraid to take bold action even within the CIA to alter its power structure, and much like Tenet, he saw an opportunity to leverage the dynamism of the private sector to address the CIA's technological needs.

Krongard, along with Jeffrey Smith, worked tirelessly to translate David's vision into a concrete plan. He was the financial architect and provided the ‘street cred’ needed to navigate both Washington and Wall Street given his previous track record as a Marine veteran and a tech-focused banker.

[4] Norman Augustine: The Industry Titan

To build an organization unlike any other, the CIA needed a board that was both visionary and pragmatic.

Norman Augustine, the former CEO of Lockheed Martin, was the perfect choice to lead this effort. Augustine was a legend in the aerospace and defense industry, a man who understood the intricacies of government contracting and the importance of technological innovation.

His career spanned the heights of American aerospace innovation. Starting off right out of Princeton (after getting both his bachelors & masters from the NJ-based university) at Douglas Aircraft, he rose to chief engineer, contributing to early missile defense and space exploration efforts. In the Pentagon, he focused on tactical missiles and land warfare systems as Assistant Director of Defense Research and Engineering, later influencing Army R&D as Under Secretary. Joining LTV, Augustine led advanced programs, likely including anti-satellite weapons, ballistic missile defense, and sensor technologies.

As CEO of Martin Marietta, then Lockheed Martin (post the merger), he oversaw iconic projects such as the F-22 and F-35 stealth fighters, the Titan IV rocket, and the modernized C-130J transport. He also was known as a vocal advocate for missile defense and advanced satellite programs. Augustine's impact wasn't just in building hardware. He restructured the aerospace industry and fiercely advocated for R&D investment, ensuring America's continued technological leadership. He was a key player in the development of some of the most important pieces of technology for the defense and space apparatus of the US.

But he was more than just a corporate titan; he was known as a maverick, someone who wasn't afraid to challenge conventional wisdom. Tenet and Krongard tapped Augustine not for his industry connections, but for his strategic acumen and his ability to assemble a team of brilliant minds who could help them create a new model for government-industry collaboration.

[5] Gilman Louie: The Visionary CEO

The final piece of the puzzle was finding the right leader to execute this audacious vision. The board, advised by John Seely Brown, wanted someone unconventional, someone who understood the language of Silicon Valley, someone who could move quickly and embrace risk.

They found their man in Gilman Louie, a computer game entrepreneur who had created his first company while still in college. Louie was not a typical candidate for a government job. He was a Democrat, a fourth-generation Chinese-American, and a veteran of the tech world, with no prior experience in the intelligence community (and no connection to the Defence or Aerospace domain unless you count his company, Spectrum Holobyte, developing the F-16 Falcon Simulator as being enough to merit such inclusion).

But he was also a visionary, someone who understood the power of technology to transform industries and even nations. He was intrigued by the CIA's willingness to change and saw an opportunity to use his skills to make a real difference. The board was captivated by his intellect, his passion, and his deep connections in the Valley. Louie became the public face of In-Q-Tel, the charismatic leader who could bridge the cultural divide between the CIA and the tech world.

[6] The All-Star Board: The “Plus Eleven”

Augustine's "killer board" was a constellation of brilliance, each member bringing a unique set of skills and experiences.

There was Lee Ault, chairman of the board and a veteran of the financial industry, providing stability and oversight. John Seely Brown, the former director of Xerox's famed Palo Alto Research Center (PARC), brought an understanding of how to foster innovation within a large organization. He also suggested bringing on a computer gamer as CEO (which would later turn out to be Gilman Louie), knowing the ingenuity inherent in that space. Howard Cox, a general partner at Greylock and chairman of the National Venture Capital Association, offered invaluable insights into the world of venture capital. Michael Crow, an academic leader with a deep understanding of the interplay between universities, industry, and government, provided a broader perspective on innovation ecosystems. Stephen Friedman, a senior principal at Marsh & McLennan Capital Inc. and former chairman of Goldman Sachs, brought financial expertise and a global perspective. Paul Kaminski, a technology expert and former Undersecretary of Defense for Acquisition and Technology, offered insights into the Pentagon's needs and challenges. Jeong Kim, a former executive at Lucent Technologies and founder of Yurie Systems, brought telecommunications expertise and an entrepreneurial spirit. John McMahon, a former president and CEO of Lockheed Missiles and Space Co. and former deputy director of central intelligence, provided a crucial link between the intelligence community and the private sector. Alex Mandl, a former chairman and CEO of Teligent and former president and CEO of AT&T, brought experience in the rapidly evolving telecommunications industry. And finally, William Perry, the former Secretary of Defense, offered a deep understanding of national security and the importance of technological superiority.

This diverse board, carefully curated by Augustine, was instrumental in shaping In-Q-Tel's unique structure and guiding its early steps. Each member brought their own unique expertise to create an organization unlike anything that had existed before.

Together, these individuals, each a leader in their own right, formed a unique team that was perfectly positioned to create and launch In-Q-Tel. They were the architects of a new model for government innovation, a model that has since been studied and emulated around the world. They dared to challenge the status quo, to embrace risk, and to forge a new path forward. Their story is a testament to the power of vision, collaboration, and a willingness to break the mold. Their legacy is In-Q-Tel, a testament to their foresight and a vital asset in America's ongoing quest to maintain its technological edge.

B. Business Model

“Investments buy the CIA access to technologies still in the womb. In-Q-Tel's board saw that if the CIA could be involved at the beginning as a technology was being developed for commercial applications, the company could be modifying it so it would be useful to both industry and the CIA. As soon as it hit the market, the CIA could buy and use it and be as current as anybody in the world." - Jeffrey Smith, In-Q-Tel’s legal counsel and ex-CIA General Counsel

So, to dissect the IQT Business Model, we will focus on key 7 aspects of its work (some of which may be restated from other parts of this article, so as to build out a comprehensive overview of how its Business Model functions.)

(1) Core Mission and Purpose

Mission: In-Q-Tel's primary mission is to bridge the gap between the U.S. Intelligence Community (IC) and the rapidly evolving commercial technology sector. It serves as a technology accelerator for the IC, ensuring it has access to cutting-edge innovations that can enhance its operational capabilities.

Purpose: To identify, invest in, and adapt emerging commercial technologies to meet the unique needs and challenges of the IC. The fund was created in response to the realization that the private sector was outpacing the government in technological development, particularly in information technology.

Not a Traditional VC: In-Q-Tel is not a venture capital fund in the traditional sense. Its success is measured by the adoption of invested technologies by the IC (so one could argue that by virtue of having such high rates of adoption of the invested technologies, it is already a success regardless of how these companies perform in the future), not by financial returns. It prioritizes strategic value for the IC over profit maximization.

(2) Structure and Governance

Non-Profit Status: In-Q-Tel is a private, independent non-profit organization. It is not a government agency, although it was established with the support of the Director of Central Intelligence.

Board of Directors: Governed by an 11-member board with diverse expertise from academia, business, and government (excluding current government employees).

Specialized Labs: Houses four internal labs focusing on specific technology domains (as on 24 December 2024):

‘BiologyNext’ is focused on how life sciences impact national security. Particular trends they are investigating at the time of this writing include novel materials, sensors, laboratory automation, big data analytics, and genome editing.

‘CosmiQ Works’ is focused on new trends in commercial space technology. Their current key investigation areas are satellite data analytics, communications and payloads for small satellites, mission management, and content delivery. They have a very novel partnership approach to initiating projects that solicits project ideas, participation, and co-funding from the private sector.

‘Cyber Reboot’ is based upon the premise that despite the very large amount of public- and private-sector resources being spent on cybersecurity, the number of successful cyberattacks is increasing. Their research focuses on cybersecurity doctrine, awareness, and attribution to be able to impose cost on attackers.

‘Lab41’ is conducting research in big data analytics while itself being an experiment in collaboration. It is located in Silicon Valley and has a unique 5-step process to conducting its projects. While criteria for a good problem are defined by government customers, problem recommendations can come from anywhere, including private-sector partners. Once a problem is identified, they do research to find the leading experts in related areas. They reach out to these experts and build a solution team and plan. A diverse team can then be formed to develop solutions to the challenge problem. All resulting software is treated as open source and published on GitHub. Results of the research are advertised around relevant communities via publications, sponsored events, and other presentations.

These labs enhance In-Q-Tel's technical due diligence, track emerging technologies, and engage with the broader tech community.

(3) Relationship with the Intelligence Community

Primary Customer: The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) is In-Q-Tel's primary funder and customer - this is established through a charter and a contract. The charter establishes the purpose of the relationship, that is, the overall technical and program planning and management to ensure applicability and transfer of In-Q-Tel’s solutions to the CIA’s problems.

Other Customers: Serves 10 other IC agencies, including the DOD's J39, National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency, National Security Agency, and National Reconnaissance Office.

Formal Agreements: The business arrangement between the CIA and In-Q-Tel is formed by both a charter agreement and a contract, whose form is CIA-unique, but roughly comparable to an Other Transaction Authority (OTA) in DoD practice. There is plenty of debate and analysis on the aspect of this “Other Transaction Authority” with a ton of case law and policy critique so I won’t delve deeper into it. Relationships with other agencies are established through memoranda of understanding via the CIA.

Contractual Agreement with CIA: In-Q-Tel’s contract is funded annually, and In-Q-Tel is given a new problem set in each cycle (1 April to 31 March). This set is basically a fixed-price level of effort arrangement with no award fees or other incentives for spectacular success, although In-Q-Tel can reward its own employees for particularly noteworthy accomplishments. The patent and data rights provisions are fairly traditional, although an option for agency specific rights exists under certain circumstances.

Problem-Driven Approach: IC agencies provide In-Q-Tel with annual "problem statements" outlining their mission and baseline requirements. In-Q-Tel then identifies technologies that best address these needs, without being constrained by specific technical specifications at the outset.

In-Q-Tel Interface Center (QIC): A dedicated center within the CIA that facilitates communication, disseminates information about investments to relevant groups, and manages the transfer of technologies from portfolio companies to the government. The QIC is advised of proposed In-Q-Tel investments. However, its consent is not required for In-Q-Tel to make an equity investment. In practice, if a difference of opinion arises between the QIC staff and In-Q-Tel about a proposed investment, the matter is scrutinized again by the In-Q-Tel Board of Trustees.

(4) Investment Strategy and Process

Funding: Receives approximately $120 million annually from the IC, with the CIA providing the largest share but less than half of the total. Other agencies contribute funding through the CIA. Co-funding by multiple agencies is common, increasing In-Q-Tel's investment capacity.

Investment Size and Frequency: Makes about 50 new investments per year, averaging $1.5 million (maximum $3 million) per investment, totaling around $75 million in annual investments. (based on last government-backed, publicly available verifiable figures)

Co-Investment Model: Always co-invests with private venture capital funds, maintaining a minority investor position in all investments. This approach mitigates risk and leverages the expertise of the private sector. Also helps IQT keep a high private-to-public capital ratio that drives down technological acquisition cost.

Investment Instrument: Uses equity warrants, which are guarantees to buy stock at a fixed price later. This grants In-Q-Tel flexibility and avoids immediate voting rights, aligning with its non-competitive stance.

Investment Focus: Primarily targets Series A and B funding rounds to avoid competition with later-stage investors and to influence technology development early on.

Due Diligence: Conducts rigorous technical due diligence to mitigate technical risks, relying on co-investors for other business risk assessments. The thorough vetting process creates a "halo effect," attracting further investment and validating the technology for the IC.

Disbursement: Funding is provided in tranches over time, contingent on the company meeting pre-defined milestones.

Timeframe: The time from investment to product delivery varies greatly between 12-18 months for software and significantly longer for hardware technologies.

Employee Fund: Employee compensation includes 10—25% of an employee’s total compensation, depending on position, going into a mandatory employee’s investment fund. For every $3 invested in a company, $1 from the employee’s fund is also invested. The rationale of this approach is to emulate the financial driver of the VC model and motivate employees to make the best possible investment decisions on behalf of In-Q-Tel and its government customers. Essentially, “skin in the game” to bring accountability and align incentives.

(5) Operational Model and Value Proposition

Technology Accelerator: Functions as a strategic technology accelerator for the IC, rather than a traditional profit-driven VC fund.

"Halo Effect": In-Q-Tel's investments signal to the market that a company is developing a valuable technology, attracting additional investment from other VC firms. $28 in private capital for every $1 invested by IQT.

Non-Recurring Engineering Support: Provides funding to portfolio companies to adapt their technologies to meet specific IC requirements, such as security or classification needs. This helps bridge the gap between rapid commercial development and the IC's stringent requirements.

Market Intelligence: Provides the IC with valuable insights into emerging commercial technologies and trends, keeping them abreast of developments that could impact their missions.

Relationship Building: Cultivates strong relationships with startups, VC firms, and the broader technology ecosystem.

Cost Savings for the IC: By identifying and adapting existing commercial technologies, In-Q-Tel saves the IC from having to invest heavily in internal R&D for those specific problem areas.

[More on this in subsequent parts]

(6) Performance Metrics and Success Criteria

“Return on Technology” (ROT) focused - See metric (8)

IC Adoption: The primary measure of success is whether the IC ultimately purchases and adopts the technologies developed by In-Q-Tel's portfolio companies.

Commercial Success Not Enough: An investment is considered unsuccessful if the technology is commercially successful but not adopted by the IC, or if the company fails.

Strategic Alignment: Prioritizes investments that align with the IC's long-term strategic needs and operational challenges.

(7) Addressing Concerns and Building Trust

Non-Competitive Approach: In-Q-Tel has addressed initial concerns about competing with private VC funds by:

Focusing on early-stage investments (Seed, Series A and B).

Maintaining observer status on company boards (no voting rights).

Investing through equity warrants.

Refraining from setting valuations or knowingly competing for investment opportunities.

Openly sharing information with other investors.

Positive Reputation: Through these measures, In-Q-Tel has built a positive reputation within the investment community that have given it a “halo effect” on most of its investments, i.e. investment from In-Q-Tel is seen as a larger signal of validation/tech affirmation by the market.

(8) The Return on Technology (ROT) Metric

Success at In-Q-Tel is measured by the return on technology. This success standard depends on whether In-Q-Tel:

“Deliver[s] value to the Agency through successful deployment of high impact, innovative technologies;

Build[s] strong portfolio companies that will continue to deliver, support and innovate technologies for In-Q-Tel’s [Intelligence Community (IC)] clients;

Creat[es] financial returns to fund further investments into new technologies to benefit the Agency, IC and federal government” (In-Q-Tel, 2005a).

C. Quantifying Impact

So one of the pitfalls of analyzing a governmental strategic investor in a sector as secretive (and pertinent) as intelligence and national security is that not every investment made can be tracked accurately - or be available publicly.

Even then, let’s use the IQT website as the source of our information and quantification efforts.

Here is what IQT says about their own impact - speaking to what they have achieved in ~25Y of scouting, investing, and accelerating dual use companies3:

Transitioned 500+ portfolio technologies to government partners.

Invested in and supported 750+ transformative technologies, to date.

Backed 50+ companies now valued at over $1 billion, showcasing a keen eye for potential. (Who does not love a Unicorn in the startup space)

Sought-after partner with 3,000+ co-investors signaling that private investors treat In-Q-Tel as an “affirmation” of value. Barry Lefew, the VP of Government Platform Accelerator at In-Q-Tel quotes that "For every dollar that In-Q-Tel invests there's usually $28 of commercial Venture Capital that's invested along with us."4

In-Q-Tel’s investment in over 50+ unicorns in its 25Y lifespan [approx ~2 unicorns created for each year spent in operation] is actually impressive given its (a) budget constraints (i.e. the capital deployed); (b) the niche focus that they are operating with; and (c) the obvious synergy that they need to find with their IC partner agencies.

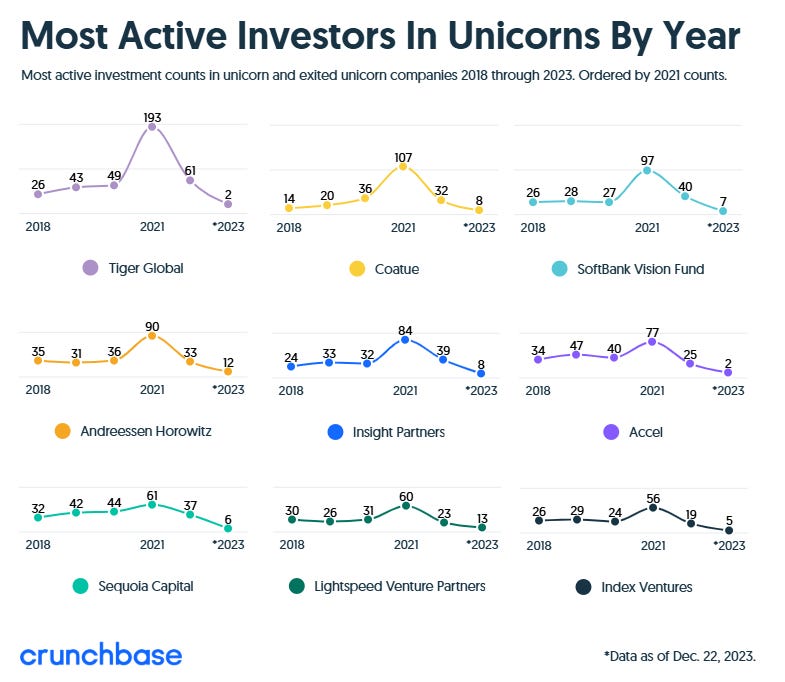

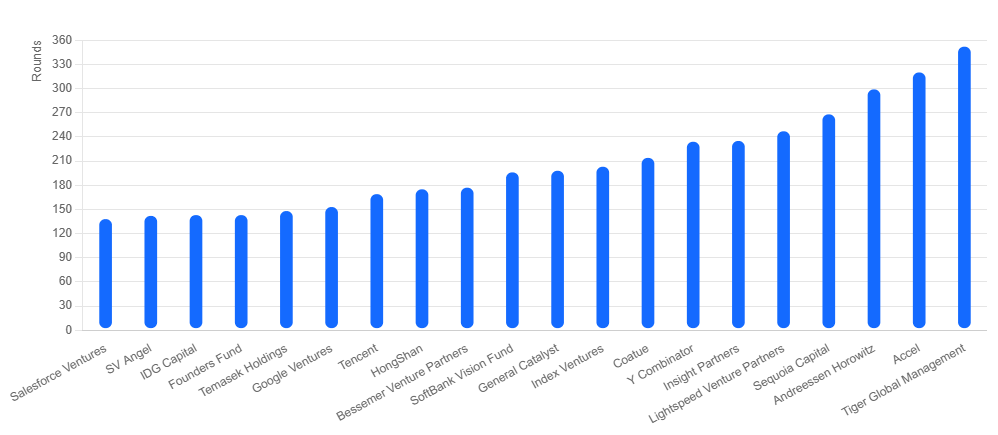

Nonetheless, this is nothing close to what private investors achieve - refer to the Unicorn leaderboard from Crunchbase (last version is 2023), but these numbers are nothing to balk at.

In-Q-Tel is still quite some distance off the most active investors in Unicorns (see updated data below). For example, Salesforce Ventures (the CVC) has invested in almost 2.5x the number of unicorns as In-Q-Tel. However, no other governmental entity or government-backed VC comes even close to matching In-Q-Tel. Moreover, these deal-counts are also for funds that are multi-stage or sector agnostic (as most large funds tend to become once they reach beyond a certain AUM).

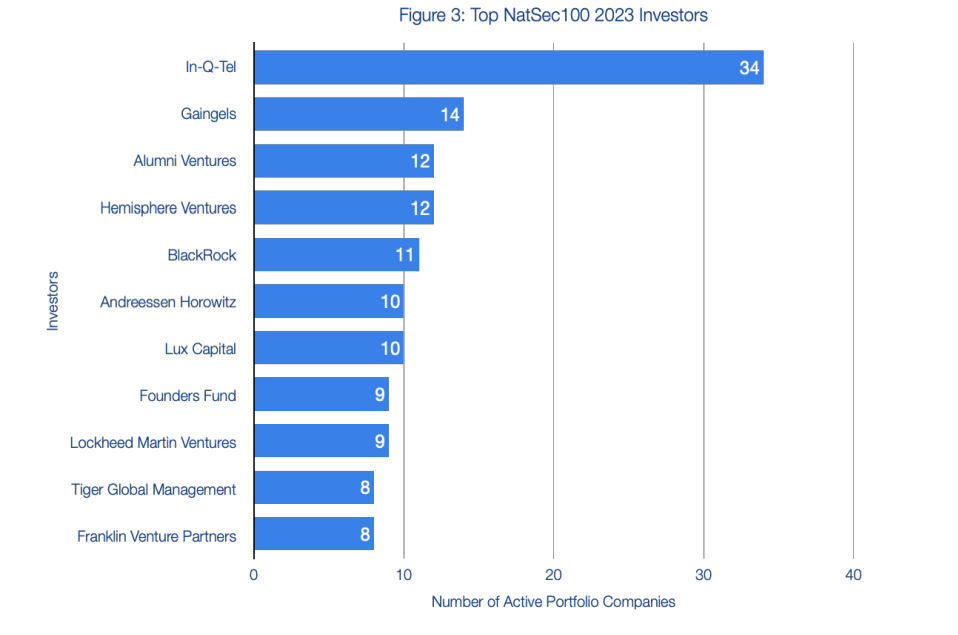

There is more - if we need validation (specifically from the National Security community within which IQT operates):

The Silicon Valley Defense Group (SVDG) releases a report on the top National Security startups / companies that are making a dent (the “NatSec 100” for each year). SVDG reported that IQT had invested in 34 companies included in SVDG’s inaugural list (from 2023) of top 100 defense and dual-use technology startups backed by venture capital firms.

For 2024, there seems to be further improvement (if marginal) as they note that IQT has invested in 35 of the 100 companies listed in the NatSec 100 for 2024.

D. IQT - Lone Star at the Intersection of Gov, Strategy & Investing?

"The CIA didn't quite know what it wanted-it wasn't a federally funded research and development center, it wasn't procurement, it wasn't in-house" - Gilman Louie, IQT's 1st CEO [Source]

So, In-Q-Tel is not “venture capital” speaking in a traditional sense.

They call themselves “Venture Catalysts” which, given their focus and early-stage involvement, does make sense.

Given its operational style at the intersection between government, strategy and investment, I would classify In-Q-Tel as a “Government Strategic Investor” borrowing on the taxonomy from RAND.

Let me outline why In-Q-Tel (and GSI programs) in general have an edge when it comes to building sector + use-specific technology and acquiring it. In this section, while I may specifically mention GSI, do note that these are aspects that are equally true of IQT as well - since we are establishing its role as a GSI.

GSI programs are distinguished from traditional venture capital by their primary objective: to advance the mission of a sponsoring government agency through strategic investments in private companies. While financial return remains a consideration, it is subordinate to the overarching goal of acquiring or developing technologies that directly address critical government needs. This mission-oriented focus shapes every aspect of GSI operations, from organizational structure to investment strategy.

Let’s dig into some key features of GSI initiatives, all of which are vividly exemplified in the IQT model.

Mission-Driven Innovation: GSIs prioritize strategic investments that enhance a sponsoring agency's capabilities over mere financial returns. For In-Q-Tel (IQT), this means focusing on technologies that directly address the evolving needs of the Intelligence Community (IC), even if it means forgoing commercially successful ventures that lack strategic relevance.

Public-Private Bridge: GSIs also operate at the intersection of public and private sectors, maintaining the agility of a venture capital firm while remaining deeply connected to their government sponsor's mission. IQT's non-profit structure, independent of the CIA yet aligned with its goals, enables it to translate IC needs into actionable investments and facilitate technology transfer.

Information as an Asset: GSI involvement in venture capital provides the government with unique access to information about emerging technologies, market trends, and potential threats. This "insider" knowledge is a core part of IQT's value, allowing it to anticipate technological shifts and identify risks before they fully materialize.

Flexible Operations via "Other Transaction" Authority: GSIs like IQT leverage "Other Transaction" (OT) authority to bypass the rigid Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR). This enables them to engage with innovative startups through flexible agreements tailored to both the company's and the government's needs, particularly regarding intellectual property.

Dedicated Interface for Seamless Communication: GSIs use a dedicated interface, like IQT's Interface Center (QIC), to bridge the gap between the government and the private sector. The QIC translates classified government needs into unclassified "problem sets" for IQT and champions the adoption of portfolio technologies within the IC.

Holistic Support Beyond Funding: GSIs provide portfolio companies with more than just capital, offering strategic guidance, mentorship, and access to networks. IQT assists companies in refining their offerings, navigating the government market, and connecting with potential customers and investors, recognizing that startups need comprehensive support to succeed.

Impedance Matching for Innovation Flow: GSIs act as "impedance matching" mechanisms, ensuring a seamless flow of innovation from the private sector to the government. IQT's structure facilitates this by effectively communicating IC needs to the private sector and tailoring innovations to meet those needs, bridging cultural and bureaucratic divides.

In-Q-Tel: GSI but Better?

In-Q-Tel embodies all the defining characteristics of a GSI. It is mission-driven, prioritizing the needs of the IC above all else. It operates at the intersection of the public and private sectors, leveraging the agility of a venture capital firm while remaining deeply connected to its government sponsor. It provides its portfolio companies with not only financial resources but also strategic guidance, access to a unique network, and a deep understanding of the government market. And it does all of this while operating under a unique legal framework that allows it to move quickly and decisively in a rapidly evolving technological landscape.

Despite generally being a GSI Model, IQT has had vastly varied results when compared to other GSI models (such as NASA’s Red Planet Capital and the US Army’s OnPoint Technologies).

Let’s try to understand why that is.

(a) Why NASA’s RPC failed when IQT didn’t

IQT's success and RPC's failure, despite similar structures, boil down to two key factors: political support and strategic alignment. While both aimed to leverage private sector innovation for government purposes, IQT enjoyed strong backing from key stakeholders and a clear, focused mission, while RPC lacked both.

1. Political Champions vs. Skepticism:

IQT: From its inception, IQT enjoyed strong support from the CIA's leadership, including Director George Tenet. This high-level backing provided crucial political cover, allowing IQT to navigate bureaucratic hurdles and overcome initial skepticism about the government's role in venture capital. The establishment of the QIC, staffed by senior CIA officials, further solidified this support and ensured alignment with the agency's strategic priorities. This internal advocacy was vital in securing continued funding and operational autonomy.

RPC: In contrast, RPC faced significant resistance from the Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) and the Office of Management and Budget (OMB). These powerful entities questioned the fundamental premise of government involvement in venture capital, raising concerns about the appropriate use of taxpayer funds and the potential for market distortion. This lack of high-level support left RPC vulnerable to budgetary cuts and ultimately led to its premature demise.

2. Strategic Focus vs. Diffuse Objectives:

IQT: IQT's mission was laser-focused: to identify and invest in cutting-edge information technologies that could enhance the CIA's intelligence capabilities. This clear strategic focus allowed IQT to develop deep expertise in relevant technology areas, build strong relationships with key players in the venture capital community, and effectively target its investments. The "Q" process, while not without its flaws, provided a framework for aligning IQT's investments with the IC's specific needs and accelerating the transition of technologies into operational use. This tight coupling between IQT's mission and the CIA's needs was a key driver of its success.

RPC: RPC's objectives were more diffused, encompassing a broad range of technologies, including advanced materials, electronics, and biomedical devices, for space exploration. While these areas were certainly relevant to NASA's mission, the lack of a singular, overarching strategic focus made it difficult for RPC to develop deep expertise, build a cohesive investment strategy, and demonstrate tangible impact. The absence of a clearly defined process for prioritizing investments and integrating them into NASA's operations further hampered RPC's ability to gain traction and build momentum - and this is generally considered an extremely vital element of the “Q Process” that we delve into later). The broader range made it more difficult to build internal consensus and garner support amongst stakeholders. It also made it easier for opponents of government VC to paint the effort as non-essential by picking apart the individual justifications.

To be fair, RPC could have been a very different story because its existence span was so short and marred with so many issues. They only invested in one company called ‘AlterG’, that made treadmills for physical therapy.

For eg., Lisa Lockyer, the Acting Deputy Director of Innovative Partnerships who ran the interface center at NASA Ames, reported that for every dollar RPC invested in AlterG, the private sector invested over $155. Because RPC operated for less than a year and invested in only one company, evaluating its structure and potential for success is difficult. Its one investment, $800,000 in AlterG, helped that company leverage $12.4 million in private VC6. AlterG’s products are being sold both commercially and to NASA. Whether NASA needed to make an equity investment in the company in order to procure the product is unclear, but a lot of that would have also been determined during the erstwhile operation of RPC.

(b) Why OnPoint Technologies failed when IQT didn’t

This difference in outcomes, despite initial similarities, can be attributed to two primary factors: sustained funding and institutionalization within the sponsoring agency.

1. Sustained Funding and Financial Viability:

IQT: IQT benefited from consistent and substantial funding from the CIA and the broader IC. This allowed IQT to build a robust portfolio, weather market fluctuations, and demonstrate long-term value. Critically, IQT also established a mechanism for generating returns on its investments, which could then be reinvested in new ventures, ensuring its long-term financial viability and reducing dependence on continued appropriations. This created a virtuous cycle of investment, return, and reinvestment, further strengthening IQT's position within the IC.

OPT: OPT received an initial allocation from Congress but lacked a mechanism for securing ongoing funding. The one-time $25 million allocation, while significant, proved insufficient to sustain long-term operations and build a diversified portfolio. The absence of follow-on funding limited OPT’s impact and ultimately constrained its ability to demonstrate its value to the Army. The lack of a self-sustaining financial model meant that OPT's future was always precarious, subject to the vagaries of the budget cycle.

2. Institutionalization within the Sponsoring Agency:

IQT: IQT became deeply embedded within the CIA's operations through the establishment of the QIC. This dedicated interface, staffed by senior CIA officials, facilitated communication, aligned IQT's investments with the agency's strategic priorities, and accelerated the integration of IQT-funded technologies into operational use. The QIC acted as a powerful internal advocate for IQT, championing its successes and ensuring its continued relevance to the CIA's mission. This deep integration into the IC's structure was crucial for IQT's long-term success.

OPT: While OPT had a relationship with the Army's Communications Electronics Command (CECOM), it lacked the deep integration that IQT enjoyed with the QIC. There was another issue7: it was a for-profit initiative. This did two things: (a) It took away from the “mission-oriented” approach of IQT and made it more financial-driven (in that sense one could even argue if it would meet the criteria for a pure-play government strategic investor at all); and (b) made it more challenging for OPT to align its investments with the Army's evolving needs and to effectively transition technologies into operational use. The absence of a dedicated internal champion within the Army meant that OPT often struggled to gain visibility and secure the necessary resources and support. This lack of institutionalization ultimately hampered OPT's ability to demonstrate its value and secure its long-term future.

Additional Contributing Factors:

Mission Focus: IQT's narrower focus on intelligence-related technologies likely contributed to its success. This allowed IQT to develop deeper expertise in specific technology areas and build stronger relationships within the venture capital community focused on those areas. OPT's broader mandate, encompassing a wider range of technologies, may have diluted its focus and made it more challenging to demonstrate clear impact.

External Environment: The timing of IQT's launch, coinciding with the rise of the internet and the growing importance of information technology, likely played a role in its success. This created a fertile ground for investment and a greater receptiveness to IQT's mission within the IC. OPT, launching shortly after 9/11, faced a different environment, one characterized by shifting priorities and budgetary constraints, which may have made it more difficult to secure sustained funding and support.

E. Operational Aspects

“The organization spots common tech capabilities (or “genes”) across multiple different products and enables engineers to combine these and create whole new solutions (“recombinant genes”) to feed to its tech hungry customers.” [Source] - Ravi Pappu, the CTO of In-Q-Tel comparing the venture catalyst to a Genome.

The reason I opened with this particular description from Ravi to define In-Q-Tel’s operational approach is twofold: (a) First, it goes beyond the usual “Venture Capital for IC” descriptor that is used to define In-Q-Tel; and (b) I think biological systems / genetics (as a discipline) is an extremely interesting way to analyze funds and the private capital market. [More on this later as I get into the “Questions Still Unanswered” section of this piece]

For instance, the term "genes" here refers to foundational capabilities. These are core functionalities like advanced sensors, secure communication protocols, novel materials, or unique data processing algorithms that can be re-purposed. This implies that In-Q-Tel's focus isn't on funding end products, but rather, the building blocks that can be combined in myriad ways. It's a much deeper level of abstraction than simply buying a cool new gadget through an acquisition channel - which I think separates it from the traditional government procurement vehicles.

The creation of “recombinant genes” is where the crux of the true brilliance lies. In-Q-Tel doesn't just acquire individual technologies; it actively facilitates the recombination of these capabilities. So this is much more than finding a ‘product’ that perfectly fits a need. It's about creating solutions that were previously unimagined. The "recombinant" aspect highlights the dynamic nature of their work; it's about engineering new functionality by combining existing elements in novel ways and utilizing a collaborative environment, possibly including engineers from the funded startups working alongside IC experts to craft these “recombinant genes”. This is also where the QIC also comes in - since it is composed mostly of liaisons from different departments of the intelligence community that In-Q-Tel works with.

It also shifts the IC's role from passive buyer to active consumer with a dynamic need for solutions.

The IC may not always know the precise solution they need, but rather understand their underlying needs or capability gaps. In-Q-Tel serves as a translator that maps basic capabilities to the IC’s evolving requirements. This also hints at the ability to rapidly adapt to new threats and requirements due to the fundamental capability focus. This also means that startups working with In-Q-Tel are not simply selling a product. They are contributing a "gene" – a reusable building block. This means their technology might be adapted and deployed in ways they hadn't anticipated, extending their impact and perhaps allowing for multiple "recombination(s)". This implies In-Q-Tel may be more concerned with their potential rather than immediate market viability.

(1) Operating Flow + Stack for In-Q-Tel

While this image offers a simplified depiction of a complex system, it effectively captures the essence of how In-Q-Tel operates and interacts with the CIA, portfolio companies, and the broader technology ecosystem.

Let me explain (to the best of my limited ability):

1. The Foundation: The Investor (CIA)

At the heart of the model lies the Investor, which in this case is the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA).

The CIA provides the financial fuel that powers the entire In-Q-Tel engine. This funding is represented in the diagram as $(X+f).

X: This portion of the funding represents the capital allocated for two primary purposes:

Investments: Equity investments in portfolio companies, giving In-Q-Tel an ownership stake.

Operational Expenses: Funding the day-to-day operations of In-Q-Tel, including salaries, infrastructure, and other overhead costs.

f: This represents the management fee paid to In-Q-Tel for its services. It compensates In-Q-Tel for managing the investment process, identifying promising technologies, and facilitating the transfer of those technologies to the CIA.

Crucially, the CIA's role extends beyond simply providing funds. It also defines the strategic direction through the "Problem Set," a collection of prioritized technology needs that guides In-Q-Tel's investment decisions. The CIA, through the QIC, also acts as the end-customer, receiving and integrating the developed technologies.

2. The Engine: The Investment Manager (In-Q-Tel)

In-Q-Tel acts as the Investment Manager, operating as a not-for-profit entity with a unique mission: to bridge the gap between the Intelligence Community and the rapidly evolving world of commercial technology. It's not a traditional venture capital firm, although it shares some similarities. Its primary focus is on strategic impact—delivering technology solutions to the CIA—rather than maximizing financial returns.

In-Q-Tel's multifaceted responsibilities are represented in the flowchart:

Develop Investment Thesis (Blue Box): In-Q-Tel, in collaboration with the QIC, develops investment theses based on the CIA's Problem Set and broader market trends. These theses guide the organization's search for promising technologies.

Generate Deal Flow (Green Box): In-Q-Tel actively scouts for potential investment opportunities. It leverages its extensive network within the venture capital community, academia, and industry to identify companies developing innovative technologies relevant to the CIA's needs.

Conduct Due Diligence (Green Box): Before making any investment, In-Q-Tel conducts rigorous technical and business due diligence on potential portfolio companies. This involves evaluating the technology, the company's management team, the market opportunity, and the potential for the technology to be adapted for the CIA's use.

Negotiate Investment (Green Box): In-Q-Tel negotiates the terms of investment with portfolio companies, including the amount of funding, the type of investment (equity or work program contract), and any intellectual property rights agreements.

Monitor Investment (Green Box): After making an investment, In-Q-Tel actively monitors the progress of the portfolio company. This often involves taking a board observer seat, providing guidance and support, and tracking the development of the technology.

Harvest Investment (Green Box): While financial return is secondary, In-Q-Tel does manage exits from investments, typically through acquisitions or IPOs. Any returns are reinvested back into In-Q-Tel or used to support strategic initiatives within the CIA.

3. The Bridge: QIC (In-Q-Tel Interface Center)

The QIC (represented by the yellow box labeled "Customer" under the CIA) is a critical component of the In-Q-Tel model. It's a small team within the CIA that acts as a bridge between the classified world of the Agency and the unclassified operations of In-Q-Tel.

Key functions of the QIC:

Translate Agency Needs: The QIC works with various CIA directorates to understand their technology needs and translates them into actionable "problem sets" for In-Q-Tel. This is a crucial step, as it ensures that In-Q-Tel's investments are aligned with the Agency's strategic priorities.

Facilitate Communication: The QIC acts as a conduit for information flow between the CIA and In-Q-Tel. This includes sharing classified information with In-Q-Tel personnel who have the necessary security clearances, as well as communicating In-Q-Tel's progress and findings to the relevant stakeholders within the Agency.

Provide Oversight: The QIC monitors In-Q-Tel's activities, ensuring that they are consistent with the terms of the charter agreement and the CIA's overall mission.

Champion Technology Transfer: The QIC plays a vital role in facilitating the transfer of technology solutions from In-Q-Tel's portfolio companies into operational use within the CIA.

4. The Innovators: Company (Portfolio Companies)

The Portfolio Companies (represented by the orange box) are the heart of the innovation ecosystem. These are typically small, agile, technology-driven companies that are developing cutting-edge products and services. In-Q-Tel invests in these companies, providing them with both funding and strategic guidance.

Two Primary Forms of Funding:

Equity Investment ($dX): In-Q-Tel takes an ownership stake in the company, similar to a traditional venture capital firm. This provides In-Q-Tel with a financial interest in the company's success and a voice in its strategic direction. The 'd' is a percentage of the total investment.

Work Program Contracts ($(1-d)X): These are funds allocated for specific development work tailored to meet the CIA's needs. This is often used to adapt existing commercial technologies for government use. The 'd' is a percentage of the total investment. Therefore, 1-d, is the inverse.

5. The Beneficiary: Customer (CIA and Broader Intelligence Community)

The ultimate Customer is the CIA and, by extension, the broader Intelligence Community. They benefit from the technologies developed and adapted by In-Q-Tel's portfolio companies. The diagram represents this with a flow of "Product, service" from the Company to the Customer.

6. The Flow of Value (Green Arrows in the flowchart):

The green arrows in the diagram represent the flow of value among the different players. This includes:

Funding: The flow of funds from the CIA to In-Q-Tel, and then from In-Q-Tel to the portfolio companies.

Product/Service: The portfolio companies develop and deliver products and services, with a portion tailored to meet the CIA's specific needs. This flow is represented by the arrows going from the "Company" box to the "Customer" box, and from the "In-Q-Tel" box to the "Company" box (representing work program contracts).

Information: In-Q-Tel gains valuable insights into emerging technologies and market trends through its due diligence and monitoring activities. This information is then shared with the CIA through the QIC, represented by the bi-directional arrow between "In-Q-Tel" and "QIC."

Liquidity Event: When a portfolio company is acquired or goes public (represented by the cloud shape), In-Q-Tel may realize a financial return on its investment. The arrow from the "Company" box to the "Liquidity event" cloud, and the subsequent arrow to the "Investor" represents this flow.

(2) Operating Parameters

This multi-directional flow of value has also meant that certain “Operating Parameters” have de-facto come into play (or have been evolved deliberately) that In-Q-Tel has designed itself to conform to in order to fulfill its mission:

agile, to respond rapidly to Agency needs and commercial imperatives;

problem driven, to link its work to Agency program managers;

solutions focused, to improve the Agency’s capabilities;

team oriented, to bring diverse participation and synergy to projects;

technology aware, to identify, leverage, and integrate existing products and solutions;

output measured, to produce quantifiable results;

innovative, to reach beyond the existing state-of-the-art in IT;

and, over time, self-sustaining, to reduce its reliance on CIA funding.

F. How In-Q-Tel approaches Technical Issues & Product

In-Q-Tel uses something called “Problem Sets” to define different technological challenges facing the IC and its agencies. Though two core elements of its approach to technical issues includes the QIC (the “Interface”) and the Problem Sets.

[1] The QIC - The Interface between the IC & IQT

Central to IQT's success in understanding and addressing user needs is the concept of the "interface center". This is a dedicated team or entity that acts as a bridge between the venture arm and the end-users within the government agency. The CIA’s QIC has complete access to the details of In-Q-Tel’s deal flow.

The agency calls this interface an “impedance matching” role (See above: Point 7 for a Government Strategic Investor), but at its most fundamental, it establishes for all other government models the importance of precisely defining the technology needs, a crucial step for the venturing activity to work. Also, due to the highly classified nature of the CIA’s mission, the QIC allows In-Q-Tel to be staffed predominantly by experienced staff drawn from the private sector who do not hold security clearances. The CIA’s needs are translated for them by the members of the QIC, staff who do hold necessary clearances.

For instance, consider Buzzy Krongard's insights on In-Q-Tel's Interface Center (QIC).

The Challenge of Engagement: To put into perspective the challenge that being the “Interface” entails - at least from the perspective of someone that has been part of a government fund - let me give you the perspective of someone far more capable than I. Christine Abizaid, former head of DIUx's Austin branch, pointed out that “engaging the Department of Defense (DoD) to ascertain their actual needs was often more challenging than engaging with technology companies”. This underscores a common problem in government technology acquisition: a disconnect between those developing solutions and those who will ultimately use them.

The QIC Model: IQT's solution to this challenge was the establishment of the QIC. As Buzzy Krongard, former Executive Director of the CIA, emphasized, the QIC has been one of the most successful and important components of IQT. The QIC's two-fold role is key:

Understanding User Needs: The QIC proactively engages with agency employees across various directorates to identify their needs and pain points. This involves conducting surveys, interviews, and workshops to gather requirements and translate them into actionable "problem sets" for IQT.

Technology Discovery and Anticipation: The QIC doesn't just react to stated needs; it also actively scouts for emerging technologies that could be beneficial to the Agency. This involves attending industry events, networking with startups, and staying abreast of the latest technological advancements. The QIC then evaluates whether such technologies could potentially address current or future Agency challenges.

Specialization by Agency: The text highlights that the QIC is further divided into groups based on the specific agency it serves. For example, the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (NGA) has its own QIC focused exclusively on geospatial intelligence solutions.8 This specialization allows for a deeper understanding of each agency's unique requirements and operational context.

OPT's CECOM: The success of the QIC model is mirrored in other government venture initiatives. OnPoint Technologies (OPT), which focuses on the U.S. Army, had a similar interface center9 called CECOM (Communications-Electronics Command). CECOM was intended to play a comparable role in identifying Army needs and facilitating the transfer of technology from OPT's portfolio companies.

They act as translators, bridging the gap between the language of technologists and the operational requirements of intelligence professionals. This dedicated focus on user needs is a critical success factor for government venture initiatives. It avoids creating technology for technology's sake.

[2] The “Problem Set”

Historically, government agencies, including the CIA, relied on slow, cumbersome procurement processes to acquire technology. These processes often produced solutions that were poorly aligned with user needs and operational requirements, due to vague specifications and long development cycles - which essentially meant that by the time such systems or solutions got acquired, they were on the verge of being obsolete and no longer “cutting edge”. In-Q-Tel’s Problem Set approach represents a deliberate departure from this outdated model, providing a more proactive and flexible strategy for identifying and addressing the CIA’s technology challenges.

The QIC (mentioned above) spearheads the development of the Problem Set, employing a structured, multi-stage process:

Agency-Wide Surveys: The QIC gathers input from technology leaders, service providers, and end-users across the CIA. This ensures the Problem Set reflects diverse operational perspectives and needs.

Compilation and Assessment: Data is consolidated, refined, and prioritized. Overlapping requirements are grouped, and the challenges are ranked based on their urgency and strategic importance.

Declassification and Generalization: Problems are carefully declassified and generalized to allow sharing with In-Q-Tel and commercial partners while safeguarding sensitive information.

Review and Validation: A cross-functional team of experts rigorously reviews the draft Problem Set. It is further scrutinized by the Agency Information Service Board (ISB) to ensure accuracy and alignment with agency priorities.

Executive Approval: The finalized Problem Set receives top-level approval from the Agency Executive Board, providing corporate buy-in and ensuring consistency with the CIA’s broader mission.

In-Q-Tel views the Problem Set as a "truly corporate statement" of the CIA’s technology needs, not merely a wish list. It serves as a contractual guide for In-Q-Tel’s work, providing clear direction while allowing flexibility to explore innovative solutions.10

The approved Problem Set is incorporated into the contract between the CIA and In-Q-Tel, forming the basis of their working relationship. This contractual obligation underscores the importance of the Problem Set in guiding In-Q-Tel's investment decisions and work program activities. This too has been a gradual climb - though one where IQT has displayed remarkable flexibility in adapting to critique and feedback - for instance, the first three Problem Sets (FY 1999, FY 2000, and FY 2001) were criticized for being too broad.

However, when scrutinized by BENS, the Independent Panel constituted under the Business Executives for National Security Study highlighted that a broad approach is appropriate, allowing In-Q-Tel the flexibility to explore a wide range of potential solutions11. The key is to strike a balance between providing sufficient guidance and allowing for flexibility to adapt to emerging technologies and changing Agency needs.

G. The “Q Process”

The "Q" Process, while initially criticized for its broad scope and lack of specificity, reflects IQT's unique challenge of translating classified needs into actionable investment targets. The process, with its annual iterations and revisions, is not a static framework but rather an evolving experiment, continually adapting to the IC's changing priorities [which is captured through “Problem Sets” that the IC shares with the QIC, and therefore IQT] and the ever-shifting technological landscape.

The very breadth of the Problem Set, while seemingly a weakness, allows IQT to explore a wider range of potential solutions, increasing the likelihood of discovering disruptive technologies that might not have been considered under a more narrowly defined set of requirements.

The Q process is more about identifying needs (and the types of technologies that might address them) rather than specifying them as explicit product requirements. This allows for a flexible approach to technology development and opens the door to more iterative experimentation in pursuit of a viable product.

The "Q Process" is a multi-stage framework that guides In-Q-Tel's activities, from initial needs identification to the eventual deployment of technology within the CIA. It's a structured yet adaptable process designed to bridge the gap between the fast-paced commercial technology sector and the unique requirements of the Intelligence Community.

Q0: Agency Needs Definition - The Foundation

Purpose: This is the foundational phase where the CIA's technology needs are identified, prioritized, and translated into actionable "Problem Sets." It's about understanding the "what" before moving to the "how."

Process:

Surveys and Interviews: The QIC (In-Q-Tel Interface Center) takes the lead, surveying technology leaders, service providers, and users across the CIA. They conduct interviews to gather a comprehensive understanding of the Agency's IT challenges and requirements.

Problem Set Compilation: The collected data is analyzed, and individual problems are grouped into broader "problem areas." These problem areas form the basis of the Problem Set.

Declassification and Generalization: Many of the identified problems are inherently classified. The QIC works to generalize these problems and describe them in an unclassified format, making them accessible to In-Q-Tel without compromising sensitive information.

Prioritization: The QIC, in collaboration with the Advanced Information Technology Office and the Chief Information Officer, prioritizes the problems within the Problem Set. This ensures that In-Q-Tel focuses on the most critical needs.

"Use Scenarios": QIC provides "use scenarios" to further illustrate the context and application of the identified problems.

Review and Approval: The draft Problem Set is reviewed by the Agency's Information Services Board (ISB) and then approved by the Agency Executive Board, ensuring that it represents a corporate-level consensus on IT needs.

In-Q-Tel's Role: In-Q-Tel assists in evaluating the technical feasibility of potential solutions during this phase. The approved Problem Set becomes part of the contractual agreement between the CIA and In-Q-Tel, providing a clear mandate for In-Q-Tel's activities.

Q1: Technology and Market Analysis - Scouting the Landscape

Purpose: This phase is about understanding the commercial technology landscape and identifying potential solutions that could address the CIA's Problem Set. It's about knowing what's "out there" before making investment decisions.

Process:

"Swimming in the Valley": In-Q-Tel actively engages with the technology community, particularly in Silicon Valley (though not exclusively), to stay abreast of the latest advancements. This involves networking with venture capitalists, entrepreneurs, researchers, and industry experts.

Market Research: In-Q-Tel conducts thorough market research to understand the competitive landscape, identify key players, and assess the maturity and potential of various technologies. They examine company information, technology capabilities, and current market valuations.

Technology Assessment Tiers: In-Q-Tel employs a tiered approach to technology assessment:

Tier 1: Broad market research to understand the overall landscape.

Tier 2: Company-specific research to evaluate potential investment opportunities.

Tier 3: Ongoing evaluation of the technology solution to ensure it remains viable and relevant.

"Dance Phase": This is where In-Q-Tel begins initial discussions with potential portfolio companies. These discussions focus on the technology, the company's business plan, and the potential for the technology to address the CIA's needs.

Q2: Portfolio Management - The Deal Phase

Purpose: This phase is where In-Q-Tel moves from exploration to engagement, selecting specific companies for investment and negotiating the terms of the deals. It is where they match the Agency needs to possible solutions.

Process:

Matching: In-Q-Tel matches the identified technology needs (from Q0) with the capabilities of specific companies identified during the "dance phase" (Q1).

Due Diligence: In-Q-Tel conducts in-depth due diligence on potential portfolio companies, evaluating their technology, business plans, management teams, and financial health. This is often described as more rigorous than typical VC due diligence.

Contract Negotiation: In-Q-Tel negotiates the terms of the investment with the portfolio company. This includes:

Equity Investment: Determining the amount of equity In-Q-Tel will receive in exchange for its investment.

Work Program Contract: Defining the specific development work the company will undertake to adapt its technology to meet the CIA's needs. This is often funded through a separate work program contract.

Intellectual Property Rights: Negotiating the ownership and usage rights for any intellectual property developed during the project.

Deal Closure: Once the terms are agreed upon, the deal is finalized, and In-Q-Tel makes its investment.

Q3: Concept Definition & Demonstration - Proving the Concept

Purpose: This phase focuses on testing and validating the technology through demonstrations and proof-of-concept projects.

Process:

Contract Signing: The final contract between In-Q-Tel and the portfolio company is signed.

Technology Testing and Feedback: The portfolio company begins developing the agreed-upon work product, and there's an iterative process of testing, feedback, and refinement. In-Q-Tel, QIC, and the company work closely together to ensure the technology is meeting the defined requirements.

Solution Vetting: The technology solutions are vetted against the Agency's needs and measured for their effectiveness.

Q4: Prototype and Test - Building and Refining

Purpose: This phase involves the development of working prototypes and rigorous testing in a simulated Agency environment.

Process:

Prototype Development: Portfolio companies develop prototypes based on the specifications outlined in the work program contract.

"Use Scenarios": Prototypes are tested against specific "use scenarios" that mimic real-world situations within the CIA.

Environment Replication: In-Q-Tel and QIC work to replicate the Agency's IT environment as closely as possible to ensure that the prototypes can be realistically evaluated.

Qp: QIC/In-Q-Tel Piloting - Limited Deployment

Purpose: This phase involves deploying the technology on a limited basis within the Agency to further test and refine it in an operational setting.

Process:

Technology Insertion: The technology is introduced into a specific area or unit within the CIA.

Collaboration: In-Q-Tel, QIC, and the portfolio company work closely with the end-users to monitor performance, gather feedback, and make any necessary adjustments.

Q5: Commercialization - Beyond the Agency

Purpose: While not the primary focus, In-Q-Tel encourages portfolio companies to commercialize their technologies for the broader market. This can lead to greater sustainability for the company and potentially lower costs for the Agency in the long run.

Process:

Market Assessment: In-Q-Tel and the portfolio company assess the commercial viability of the technology.

Business Development: The portfolio company, with guidance from In-Q-Tel, pursues commercialization opportunities.

Qb: End-User Piloting - Real-World Testing

Purpose: This phase involves broader testing of the technology by end-users within the Agency. This is a critical step towards full-scale deployment.

Process:

Operational Testing: End-users test the technology in an operational environment, providing feedback on its performance, usability, and effectiveness.

Refinement: The technology may be further refined or modified based on the feedback received during this phase.

Qd: Deployment & Agency Acquisition - Full-Scale Implementation

Purpose: This is the final stage of the "Q Process," where the technology is fully deployed within the Agency and integrated into its operational workflows.

Process:

Acquisition: The CIA formally acquires the technology, often through a competitive bidding process.

Deployment: The technology is deployed across the relevant Agency components.

Integration: The technology is integrated into the Agency's existing IT infrastructure and operational processes.

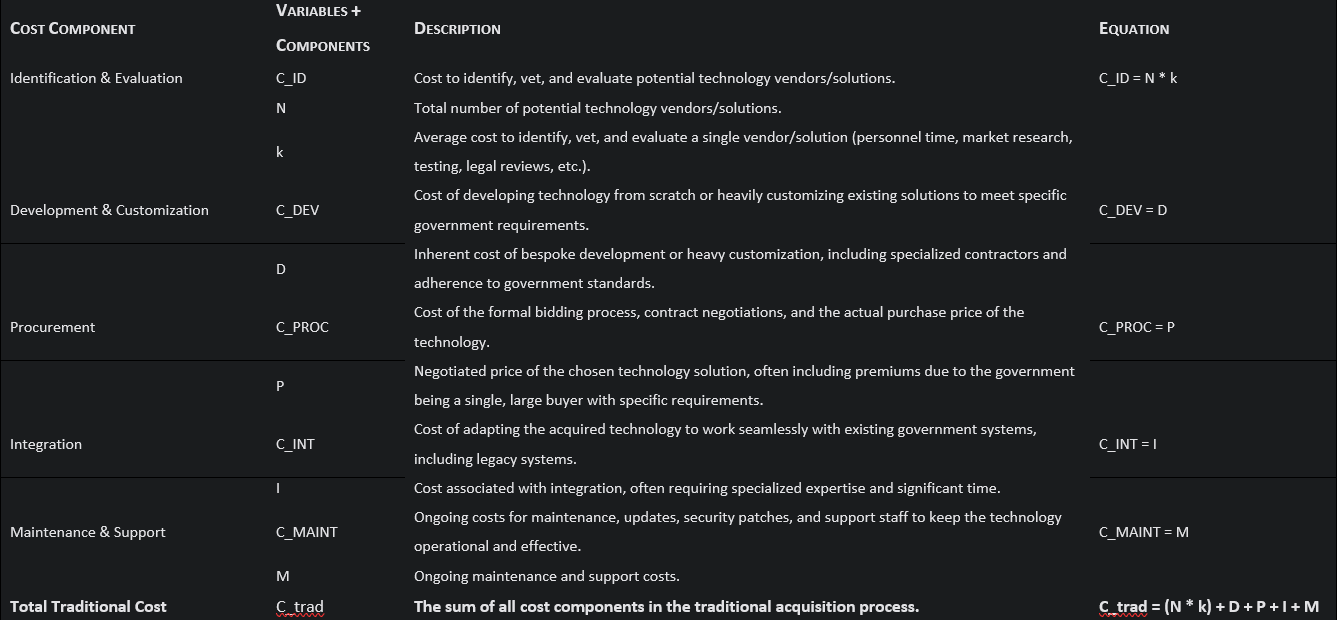

Now, let’s try to build the “Semi-Napkin Math Model” (the “SNMM”). And don’t worry, if equations aren’t your thing (or you prefer things explained more intuitively?), I lay down the cost being driven down in a more free-flowing, non-math approach in “H-2” following this next section.

H. How does In-Q-Tel drive down Technology Acquisition Cost (or Defence Acquisition Cost)

Now, let’s try to build a framework that can help us understand and break-down how In-Q-Tel brings down the cost of Defence Acqusition/Technology Acquisition from the lens of the government (specifically, the Intelligence Community and the related agencies of IQT’s network).

I am no mathematician, so we will build something called a “Semi-Napkin Math Model” (“SNMM”) which I would guess is somewhere between napkin math and actual mathematical model.

(0) Model Variables and Definitions:

C_trad: Traditional government acquisition cost (without IQT involvement).

C_IQT: Government acquisition cost with IQT involvement.

X: Total funds allocated by the government to IQT.

d: Proportion of X allocated to direct investment (equity) in companies.

(1-d): Proportion of X allocated to work program contracts (prototype development).

λ: A factor representing the efficiency of IQT's investment in finding relevant technology (probability of success per dollar invested). λ > 1 suggests IQT is more efficient than traditional methods.

N: Number of potential technology companies relevant to the Agency's needs.

k: Average cost to identify and evaluate a single technology company through traditional methods (without IQT).

c: Cost to rechannel a technology development toward government-specific needs (work program cost).

p: Probability of a portfolio company successfully developing a technology that meets government needs.

s: Probability of successful technology transfer and adoption by the government.

v: Value of the technology to the government.

r: Rate of return on investment from a liquidity event for a given company. This is net of any carry that goes to the In-Q-Tel team.

b: Expected savings on procurement due to the use of non-traditional acquisition methods.

m: Expected reduction in the cost of maintenance due to the use of commercial components.

Think of 2 routes of how technology acquisition works (from the POV of the government): “The Traditional Route” vs “The IQT Route”

So let me lay out how we are going to map out how we are going to construct such a mathematical model. We begin from:

(a) defining the cost landscape without In-Q-Tel in a traditional acquisition route, and then

(b) defining the cost landscape with the involvement of IQT in the IQT route. Finally, we move to

(c) where we calculate the cost savings from IQT > Traditional.

Clear? Let’s go.

(1) Defining the Cost Landscape Without In-Q-Tel (Traditional Acquisition)

In the absence of IQT, the government's acquisition process typically involves a well-defined, often bureaucratic, series of steps. We can model the total cost of acquisition under this traditional approach (“C_trad”) as the sum of several key cost components:

(2) Defining the Cost Landscape With In-Q-Tel Involvement

Now, let's consider the acquisition process when In-Q-Tel is involved. IQT's model fundamentally alters the cost structure by leveraging private sector innovation and a venture capital approach. The total cost of acquisition with IQT involvement (C_IQT) can be modeled as follows:

(3) Cost Savings for In-Q-Tel vs Traditional Model

The cost savings achieved by using In-Q-Tel is the difference between the traditional acquisition cost and the acquisition cost with IQT involvement:

Cost Savings = C_trad - C_IQT

Substituting the equations for C_trad and C_IQT:

Cost Savings = [(N * k) + D + P + I + M] - [X + ((N / λ) * k) + ((1 - p) * (d * X) + ((1 - d) * X)) + (P - b) + (I - m) + (M * ((I - m) / I)) - (p * s * r * (d * X))]

Yeah, this is too convoluted. Let's simplify this equation to highlight the key drivers of cost savings:

Cost Savings = (N * k) - ((N / λ) * k) // Savings from efficient identification

+ D - ((1 - p) * (d * X) + ((1 - d) * X)) // Savings from leveraging commercial development

+ P - (P - b) // Savings on procurement

+ I - (I - m) // Savings on integration

+ M - (M * ((I - m) / I)) // Savings on maintenance

- X // Initial investment in IQT

+ (p * s * r * (d * X)) // Returns from successful investments

Further simplification:

Cost Savings = N * k * (1 - (1 / λ))

+ D - ((1 - p) * d * X + X - d * X)

+ b

+ m

+ M - M + (M * m / I)

- X

+ p * s * r * d * X

Cost Savings = N * k * (1 - (1 / λ))

+ D - X + p * d * X

+ b

+ m

+ (M * m / I)

- X

+ p * s * r * d * X

Cost Savings = N * k * (1 - (1 / λ))

+ D - 2X + p * d * X + b + m + (M * m / I) + p * s * r * d * X

Interpreting the Cost Savings Equation:

So, we can state that each term in the cost savings equation represents a specific mechanism by which In-Q-Tel drives down acquisition costs:

N * k * (1 - (1 / λ)): This term represents the savings from IQT's increased efficiency in identifying and evaluating technologies. If λ > 1, this term is positive, indicating cost savings. The higher the efficiency factor (λ), the greater the savings.

D - 2X + p * d * X: This term captures the savings (or potential costs) related to development.

D: The cost of traditional development, which is avoided when IQT successfully identifies suitable commercial technologies.

-2X: Represents the initial allocation of funds to IQT (appears because it's a cost in the C_IQT calculation).

p * d * X: Represents the expected value of successful equity investments in driving technology relevant to government needs.

b: This term directly represents the savings on procurement costs due to IQT's influence.

m: This term directly represents the savings on integration costs due to the use of more commercially compatible technologies.

(M * m / I): This term represents the savings on maintenance costs, proportional to the integration cost savings.